OPEN SOURCE SCENARIOS – THREE INTERVIEWS

2001

OPEN-SOURCE SCÉNARIOS is a text published for the Traversées exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, ARC, in 2002.

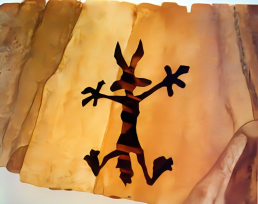

These three interviews take as their starting point the same image from the 1960s cartoon featuring Bip-Bip and the Coyote (the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote in V.O.) and were conducted in July 2001 with Stéphane du Mesnildot (film critic), Thierry Foglizzo (astrophysicist) and Nicolas Orlando (psychiatrist). This childhood image/memory is itself the source of the work Autoportrait en coyote, presented in the Traversées exhibition.

Interview with Stéphane du Mesnildot

-Stéphane du Mesnildot: « Bip-Bip et le Coyote » is a great cartoon about frustration. We have the coyote, a character who is hungry, and it shows, he’s completely starved, bristly, angular, etc., you can see his ribs. It’s a radical departure from everything Disney ever did, with its curves, cuteness and prettiness: He stops just to beep-beep, to taunt, he flies past at full speed, and all this in what I consider to be the most beautiful cartoon setting, a Death Valley that looks a bit like the landscapes in John Ford films, crossed only by a strip of tarmac road, through which no car passes, nothing at all, just the bird and the coyote. It’s an arid landscape, which reinforces the coyote’s sense of loneliness, hunger and frustration. And what’s going to happen, their story, is different from other cartoons like Tom and Jerry or even Tweety and the Pussycat, where we’re still in somewhat bourgeois, urban interiors, small suburban houses, that sort of thing, whereas here we’re leaving a domestic setting for a setting that gives the gags a modern edge. In other words, all of a sudden the camera can take a huge step back and adopt very high points of view to discover the setting…

-Boris Achour: Incredible dives into the depths of the canyons…

-S.d.M.: Yes, it’s a completely metaphysical setting, because there are so many waterfalls… so the only movement there is, between these great verticalities and horizontalities, is that given by the coyote and the bird that criss-cross this space. And what Chuck Jones introduces are the traps that the coyote receives from ACME. ACME, which is basically the company that’s in all the cartoons whenever there’s a…

-B. A.: By the way, who invented this ACME company, do you know?

-S.d.M.: No, but I have the impression that in old slapstick films there are already ACMEs.

-B. A.: Do you know if this company exists?

-S.d.M.: No, no, it’s completely invented… and so he gets traps from who knows where, which he sets up and which, incidentally, fail… Which adds to the modernity. It’s a trick we’ve seen in a lot of slapstick films, and you can see it in the Kitano film that’s just come out, Getting Any.

-B .A.: Ah yes, the huge flyswatter mounted on a bulldozer….

[LAUGHS]

-S .d.M. : Yes, that’s it, and all the gags are constructed like the preparation of a very long gag with a failed, disappointing punchline that falls completely flat. Like the gag where the guy wants to rob a bank, so he climbs to the top of the building and climbs down a rope onto the pavement opposite the entrance. And here it’s exactly the same, you can see the coyote preparing a sort of complicated trap, a bit like a Raymond Roussel mechanic, with lots of gears, cogs, things like that, and which finally concludes just with the bird flying past and then that’s it, nothing happens. So you could say that there’s a modernity to the gag, if only through the possibility of having a very, very distant point of view. We’re already in Tati’s gags, for example, systematically filmed from a great distance, where you see the gag being constructed in a minimal way, and here it’s a bit the same, the point of view allows that… there’s also an issue of the absurd, of failure… So, on the image itself, the image you’re proposing is a typical image from the end of a gag where the coyote finds itself imprinted in the stone, we can imagine that it must have propelled itself in some way to gain speed and that it went into the wall, which cut out its silhouette.

-B. A.: That’s a recurring image, whether it’s in the ground, when he falls from a great height, and in any case it’s an image that you see in lots of cartoons, or even I remember a scene in Roger Rabbit where he’s in a room and suddenly he goes at full speed and goes through a partition, the partition of a « real » house, and you see his footprint cut out very precisely in the wall. … and in lots of other cartoons you find this, characters who crash into walls or floors, who become completely flat… and who never die…!!!

-S.d.M.: Yes, they have an aberrant immateriality. In each episode, and there have been I don’t know how many episodes, the coyote « dies » about ten times, and he never dies… And as he doesn’t catch the bird, he doesn’t eat either, so it’s like an image of hell, and what’s more, there isn’t even the sentimental bond between the bird and the coyote that there might be between Tom and Jerry, or between Tweety and Big Kitty…

-B .A.: And they don’t speak: the coyote never expresses himself, and the bird just says « Bip-Bip »…

-S .d.M.: Yes, and that adds to the loneliness. There’s never any other character, and you never see who’s bringing the trap parcels. So we really have a universe that’s a bit under wraps, with the designers having fun injecting traps and things like that, where ACME is really an image of the designer or studio that propels trap-objects into this universe, which then appear and disappear without explanation. So this image is the impression of the character in his setting, a setting of rock, and you can see the talent of the designers, because if you take any small part of the rock it’s a magnificent abstraction, and what’s interesting is: where is the coyote in this image, is it even more prominent?

-B .A.: Has it gone through, is it embedded a metre deep?

-S .d.M. : In any case, it sticks to its setting, and you can see that in fact the setting of the rocks and cacti, this uninhabitable, uncomfortable setting, is actually the coyote’s setting…

-B .A.: Hostile.

-S .d.M.: Yes, the coyote is an emanation of the scenery, in fact, and it’s the bird that disturbs it: it’s colourful, it’s round, it looks friendly, and it disturbs the scenery. It’s obvious that in any story of frustration, it starts with the object of desire. If the object wasn’t there, the universe would be calm. And that really defines the coyote as an emanation of its setting…

-B .A.: The thing that really interests me about this image is that, even though every time he sets a trap it backfires and never works, and he’s always being blown up and crushed in all sorts of different ways, there’s still this recurring image of him bumping into the scenery. And if I’ve chosen this image and not one where he’s horizontal, where he’s fallen from a great height to the ground, here he’s embedded against a vertical wall, and what interests me here, by linking this image to what I want to do in the exhibition, is the hard contact in relation to the world around you, to the décor so… It’s like banging into walls… It’s the body of this coyote, something soft and alive bumping into something hard, stone, and then what does that produce? What does it do? If we do that as human beings, it won’t do that, it’ll leave a big red stain, or at least it’ll hurt a lot, and we won’t get through the wall… that’s the parallel that interests me, if we transpose that to us humans, in relation to our objects of desire… bumping into the real.

-S .d.M.: Bumping into reality, that’s basically what happens in all fantasy scenarios, but you were talking about the body, and that’s not the worst thing that can happen to it, because there are some very unpleasant things that can happen when it’s the victim of an explosion, for example: it falls into ashes, it disintegrates? But if we take the coyote’s universe as a mental universe, which is what I was trying to say earlier, that is to say that all this scenery relates to him, at the same time it relates to him, it’s a scenery that expresses his own frustration, a sterility too, and which is criss-crossed by something alive that he never manages to reach, he’s constantly referred back to his own inability… and at the same time it’s what keeps him alive never managing to catch it in fact. There’s something of that too, the only life he has is his desire in fact.

[LONG SILENCE]

-B. A.: Earlier, you were talking about hell. Would that be his hell?

-S .d.M. : Yes, it’s Tantalus in fact…

-B .A.: But this relationship with the scenery that you’re talking about, the coyote is really in symbiosis with it, they’re both practically equivalent in certain respects, in terms of aridity, sterility, harshness…

-S .d.M.: That’s why it never dies, in fact.

-B .A.: Yes, or maybe he’s already dead and in hell.

[LAUGHS]

-S .d.M. : Yes, that’s it… and no matter how much he’s pulverised or crushed, it’s never just a matter of him coming back inside himself: when he hits the rock, he’s pressed up against himself. And if there were a real death, if he disappeared, there would be transcendence… But no, he does it every time!

-B .A.: Yes, that’s right, it never moves forward. There’s no narrative in this cartoon, it’s the same thing happening all the time, and as the viewer, we know full well that he’ll never make it, that he’ll get crushed every time… It’s really a cartoon based on an idea, where everything is pushed to the extreme. It’s like starting all over again [LAUGHS], with failures and frustrations.

-S .d.M.: It’s also a kind of studio gagmen’s hell, because in Tom and Jerry they can add, let’s say, complexities, alliances of the two against the dog, etc., reconciliations, reconciliations, because in Tom and Jerry it’s more of a couple in fact, a bit of an infernal couple, whereas with the coyote you have to produce a gag and nothing else, and you can imagine these Warner Bros gagmen always having to find new traps… so at the same time it’s an outlet, producing new gags every time. And they certainly weren’t very well paid people, with perhaps the same problems as the coyote… [LAUGHS] So for me, there’s no such thing as reality, it’s just running up against your own fantasy.

-B. A.: So, contrary to what I was saying earlier, you don’t think he’s up against reality but more against himself, or another part, an emanation of himself which is rock?

-S .d.M. : Yes, that’s it. It’s something you find in a lot of films, in a lot of experimental films. For example, there’s a film called « Politic soft perception » by Kirk Tougas in which he used a trailer for a film starring Charles Bronson, called « The Mechanic ». Charles Bronson is a hitman, with a very classic story: the last mission turns out to be the most complex because of human feelings of friendship and betrayal, whereas he was just a mechanical killer who fulfilled his contracts without any qualms, hence the title… And so he grows older, he’s with a young man to whom he learns the trade but who ultimately betrays him, so that’s the film to which the trailer relates, and what’s interesting is that in this trailer there are very insistent shots of photos that Charles Bronson is given to identify the people he has to kill, and what Kirk Tougas did was to re-film the trailer, about 200 times I think, He filmed it once, then refilmed what he had filmed, and so on, and what he then presents lasts about forty minutes, with about forty refilmings, and we arrive at a serial degradation, a loss of quality, of definition of the image which becomes more and more abstract, corrodes, there are spots which appear, the shadows become denser and it takes on the appearance of a bad photocopy, until the moment when the image disappears, when everything becomes white. And so, in relation to this idea of repetition and the emaciated, gaunt appearance of the coyote, even if there is no narrative evolution in the series, we can still see it as the culmination of a cycle of degradation.

[LONG SILENCE]

-S .d.M.: And then there’s also a question of relief, which appears in this image. On the rock, there’s something really visible in relation to the flatness. Because the moments when the coyote crashes are the ones when the ‘flat’ nature of the celluloid becomes a little more apparent…

-B. A.: You mean that in the cartoon, the characters are supposed to be three-dimensional, and that when the coyote crashes it becomes two-dimensional, flat…

-S .d.M. : Yes, that’s right… And in fact it makes a flat part of the set appear too…

[LONG SILENCE]

-B .A.: Yes, and then another thing that comes to mind, which is fairly obvious, is « What happens if the coyote catches the bird? Well, if he eats it, that’s the end, that’s when it would really come to an end, because there’s only one bird, and then it would really become the valley of death, nothing would ever move again, there would never be another bird to come along, and so you have to wonder if he’s not deliberately missing his traps…

-B .A.: …so that he has something to live for…

-S .d.M. : That’s it. It’s one of the driving forces behind the series…

-B .A.: This internal contradiction in which he finds himself: he’s doing something while secretly hoping that it will fail, because if it succeeds it’ll stop.

-S .d.M. : Yes, that’s it! And in this case, he finds himself completely integrated into this motionless setting. Especially as a cartoon character, he doesn’t ‘need’ to eat, and there’s really the effect of the body without organs, you know, of Artaud and then Deleuze, i.e. all the mistreatment he undergoes, the compressions, the pulverisations show that he’s a character whose body is malleable. I remember, for example, a scene in Sam Raimi’s western, « Dead or Alive », where a character is pierced by a bullet and he sees his shadow in front of him on the ground with the hole in his stomach through which the light passes…

-B .A. : Yes, or that other film… « Death looks so good on you » where Meryl Streep is a ghost with a huge hole in her stomach through which you could see…

-S .d.M. : By the way, that was a film by Robert Zemeckis, the screenwriter of Roger Rabbit…

-B .A.: To come back to this story of our relationship with the set and our relationship with reality, you could say that reality is not something external or foreign to us that we bump into, but rather, in your opinion, something that we are an extension of, or that is an extension of us.

-S .d.M. : There’s a film I like that can be seen as talking about the construction of reality, it’s an American porno called « Hell for Miss Jones ». It’s about a very virtuous woman who commits suicide, and the guardians of hell are very annoyed because the only sin she committed was to kill herself. They’re faced with an almost administrative problem: what kind of torture can be inflicted on her? The guardian of the underworld asks her a few questions, and she explains that the only regret she has is not having experienced physical pleasure on earth. And so the guardian gives her a reprieve, sends her back to earth so that she can experience all forms of pleasure, she tries them all and in the end, when her reprieve is up, she has built her damnation, and she finds herself in hell in a room with an impotent man while she is inhabited by an unquenchable desire to make love. And the hell we couldn’t find for her she built herself, a classic Tantalus hell of frustration. And there’s perhaps a connection with this cartoon, about the construction of one’s own reality.

Interview with Thierry Foglizzo

-Thierry Foglizzo: What does it remind me of? There are things that the image inspires in me and things that your question inspires in me. The first things, directly, have more of a mechanical aspect, like a physics phenomenon. What shocked me immediately was to see that it had been embedded as it was, just like that, and that its tail or its ears had made the same imprint as its legs. If you read it with a physicist’s eye, it gives you a lot of information about the density of its tail and ears. We would have expected the tail not to mark as much as the rest.

-Boris Achour: That means that this character is homogeneous.

-T .F.: Yes, it’s homogeneously dense.

-B .A.: It’s the same everywhere! In his ears as well as in his arms and legs.

T.F.: Yes, and he’s even particular about his tail and ears: he’s rigid… And I don’t even think it’s possible to make a print as clear as that. Normally it would have been more like a tomato, it would have burst flat on its face and left the wall intact, but here it was stronger than the wall. In physics, we try to extract all the information from an image. In astrophysics, we study an image of the sky or of an object and we try to see all the information it contains, and generally the interest in observing the image comes precisely from the small details that don’t fit with what we might have expected. And that’s where the things that need explaining come from. So that’s what I saw. I haven’t done any calculations to find out what the minimum speed was for it to do that, but I don’t even know if it’s possible. I don’t have the equations to say more precisely. I also noticed that it had a chest, so it could have been a female…

-B .A. : I think it’s because it has protruding ribs…

-T .F.: Did you know that?

-B .A.: I think it’s because he’s so skinny.

-T .F.: Maybe. And then, I wasn’t too sure whether it was his moustaches, which would then be really hard, or whether he had very large jowls. It’s such an image of someone who’s hit the wall, like the expression ‘to hit the wall’, that it made me wonder about… Er… I took it personally, actually. There’s also the expression « having your nose in the handlebars », you can’t see where you’re going when you’re heading straight for the wall. My work tends to focus on very, very specific problems that are disconnected from everyday life, and it’s true that this is a question I ask myself from time to time. At what point am I so focused and absent from the real world that I’m heading straight for a wall? I don’t know to what extent, but I was thinking about it. If, on top of that, you’re telling me that you’re also going to run into the wall, into the exhibition… So maybe you too, I don’t know if you’re going straight into the wall or if you’ve already run into it…

[LAUGHS]

-T .F.: And then it got me thinking about this question of extracting information. It reminded me of something I was thinking about when I was doing this show with the dancers. A reflection on the extraction of objective information. I’m going to theorise in a vacuum, I don’t know to what extent these are banalities or not, but I have the impression that any image or any object, any reality has an objective existence, and then that it also has subjective resonances, which are complicated, very complicated, which will depend on the history of the observer, his childhood, and so on. So leaving aside all the emotional and subjective aspects, I have the impression that we can at least break down the objective aspects in orthogonal directions: for example, I can take a mechanical approach to this object. But I know that there are completely orthogonal directions. For example, the person in charge of the lighting for the show, Cathy Olive, as soon as she saw a situation, the first thing she noticed wasn’t the mechanics of the situation, it was: is the light yellow, red or blue, whereas for me the light was white. She’s going to describe the light, describe the shadows, that’s the immediate thing she’s going to see. Whereas for me, it’s more about the mechanical balance of things, or realising the extent to which positions are orthogonal… So there’s nothing in common between the perception of light and mechanical perception. I was shocked to realise how differently we see the world around us. And since it’s still an objective perception to say whether light is blue or yellow, or to describe mechanical equilibrium, I wondered whether we could break reality down into directions, according to a finite number of fairly orthogonal angles of view. I wondered whether the different ways of describing objective reality were infinite or whether there were a large number of ways of perceiving it, but a finite number, and therefore ultimately accessible. You could, for example, take a Marxist approach to a reality, or a sociological or historical approach, or you could qualify matter… Finally, during this work with the dancers, I took out my little notebook and tried to note how many directions I was able to list. Is it possible to reach a point where everything is said, still in terms of an objective scene or image? Once you’ve said all that, you’ve extracted all the information, all the meaning, you’ve stripped it away… I remember that, and faced with an image like that, I ask myself the question: can you strip it entirely of its meaning?

[SILENCE]

-T .F.: In fact, it makes me think of the compression of information in mathematics and the work of Turing. For example, numbers that can be written with an infinite number of decimal places, such as Pi (symbol SVP), can be reduced to an algorithm, to a programme capable of calculating them. And so we can construct a programme of finite length, which will ultimately occupy a small space in the computer’s memory and which will contain all the information about Pi. These are called « compressible » numbers. There are other numbers that cannot be reduced to a short program, i.e. the program that would have to be written to fully describe such a number is as long as the number itself, so there is no compression. This compression of numbers doesn’t lose any information, it’s not an approximation as in image or sound compression where a compromise is found by sacrificing certain aspects, high frequencies or small details to save memory space. So I was wondering if, by breaking down in all the directions you can imagine, it was possible to break down the meaning into a finite number of directions and reduce the information… You know what I mean… So now I’m waiting for your…

-B. A.: What you’re telling me makes me think of Perec or OULIPO… Do you know Perec’s stuff, his attempts to exhaust a place?

-T .F.: No, I haven’t.

-B .A.: OULIPO is a literary movement, the OUvroir de LIttérature POtentielle, it’s a group of people, writers, some of whom are mathematicians, who apply mathematical structures to their writing, or who set themselves very strong constraints. For example, there’s a book by Perec called La Disparition, which is written entirely without the letter e.

-T .F.: Now that I know…

-B .A.: Perec also did other things called attempts at exhaustion: he tried to describe a space, a street or whatever, as objectively as possible, or to think about the different possibilities or combinations for arranging and classifying his library. But obviously it’s impossible to exhaust the description of something in a literary way, which is why it’s called an attempt at exhaustion.

-T .F.: It’s like Queneau’s texts, isn’t it?

-B. A.: Yes, exactly, it’s like in this text where he describes a scene on a bus in all sorts of different styles… What you’re saying reminds me of that. Except that in this case it’s not compression, it’s actually the opposite, because it’s dilation; he starts with an extremely banal event, a scene on a bus, and he dilates it, not to infinity because that’s impossible, but he dilates it a lot by rewriting the same thing in forty different styles. And each time he gave the name of the style, there was the mathematical style, the metaphorical style, the romantic style, the pompier style, the vulgar style… that’s it!

-T .F.: And that wasn’t the end of it, he didn’t claim to be exhaustive?

-B .A.: No, he knows it’s impossible, it’s not a scientific approach on his part. So there’s no scientific pretence in this work, it’s just a kind of scientific game.

-T .F.: What I was wondering about was the orthogonality of the angles of view. Certain directions seem really orthogonal, like light and mechanics, or matter and colour, or matter and light. But then there are perhaps correspondences between these different directions that make it not so legitimate. It becomes arbitrary to try to project onto axes that aren’t really orthogonal. I couldn’t get my head around it, to know how legitimate or judicious it was to lay out these different branches, these different angles. There comes a point when you realise that you can’t tell them apart any more, that it becomes artificial to cut light and colour like that. But let’s just say that there are already so many categories that seem to be orthogonal to each other that it made me want to see this list of categories.

-B. A.: And in relation to this particular image, how many of these categories would there be for you?

-T .F.: Well, not that many! I thought the image was rather limited… I wouldn’t say I was able to sum it up exhaustively, but I couldn’t see that many angles. Well, the light, the mechanics, the history of the comic strip or the cartoon… There’s certainly information there that I’m missing, but let’s just say that there’s a lot less to say than if you were to take any other photo in this flat, for example. Because it’s a drawing, it’s still schematic, so it’s already pretty pared down.

-B. A. : In relation to what you were saying, it’s funny, but I hadn’t noticed at all the density of the body that you mentioned at the beginning. The fact that the ears, the tail and the rest of the body have the same density… I hadn’t noticed that at all.

-T .F.: But you’d thought it could squash like a tomato?

-B .A.: Yes, it makes sense to me. Because this image is part of the logic of the cartoon, and in this logic the characters never die: they go under a steamroller, they become flat, and then, wham! They become three-dimensional again. And when they bump into a wall, in the world of cartoons, it’s logical that they go through it, or get embedded in it, because there the laws of physics of cartoons govern, and they’re not the same as the laws of our world.

-T .F.: Yes, there are liberties in relation to these laws…

-B. A.: So the laws of this world are not the same as ours.

-T .F.: It’s true that it’s not a real coyote!

-B .A.: No, it’s not a real coyote. He’s a cartoon character, so he doesn’t die. He’s always trying to catch Bip-Bip, the Road Runner, but he never succeeds, he never dies, he never feeds… Anyway, these are different physical, physiological and mechanical laws to ours…

-T .F.: That’s true.

-B. A. : That’s another reason why I wanted to talk to you about it.

-T .F.: It’s also symbolic. A cartoon can call on a symbolic register. Whereas a real-world photo can also call on a symbolic register, but of a different order.

-B. A.: There is a symbolic order, a poetic order, a humorous order…

-T .F.: Humorous! That’s it! A humorous order, very good…

-B. A.: When you say that the potential of this image is relatively limited, I don’t entirely agree. Or rather, if you prefer, for me it’s not a problem. It’s through your work as a scientist that you first tried to envisage this image, but there’s no real point of view or good answer to this image, precisely because it’s a starting point. What interests me about talking about this image with people from different professions is that, inevitably, each of them pulls it towards their own way of analysing things. So I understand why you made that remark, but I think it might be a red herring to want to list all the different ways of analysing things. It’s not a red herring, it just reveals your own way of thinking about things, to want to analyse all the different ways of analysing this image.

-T .F.: But by adding these poetic or comic aspects, etc., do you think that the list goes on ad infinitum or don’t you know?

-B .A. : No, no, it never goes on forever! Even if I don’t know the size of this list… For example, if we take an image that you’re used to observing, an image of a galaxy or a star or whatever, it may be less rich, but for me it’s not a value in itself that it’s less rich.

-T .F.: Not at all…

-B. A. : Perhaps this one seems less rich to you.

-T .F.: Which one is less rich?

-B. A. : This one, the Coyote one.

-T .F.: Oh no, on the contrary…

-B .A.: Really, because you find the images of stars less rich?

-T .F.: Yes. The phenomena may be more complex, but the physical world is really reducible. In any case, it gives the impression of being reducible to a series of finite laws. The number of domains in physics is very definite. I was thinking about the example of the falling apple: if you see an image of a falling apple, you can account for its fall using the laws of gravitation. That’s the first aspect. After that, the fact that the apple is red is completely outside this gravitational approach. If you want to account for the fact that the apple is red, you have to appeal to the laws, I don’t know, of the life of apples, which mean that they have a probability of falling when they’re ripe, and so that gives you a new angle, a new framework for understanding the phenomenon. And then, the fact that there’s a bright little spot on the apple, it’s the laws of optics that explain that it’s lit by the sun and that it’s bright there… Point by point you’re going to be able to extract all the physical elements that describe an image, but really exhaustively, and if there’s something that escapes this list of theoretical frameworks, that’s precisely what will be interesting because it’s something that will be able to ask questions like « what are we missing? « What haven’t we understood? And we’ll have to formalise it further to be sure that this fall is ultimately consistent with our understanding of the world. That’s the kind of exhaustiveness we have in physics with objects, and that’s what I was looking for. But it’s true, given that it was already a human intention to have made this drawing, that it’s a living world, it’s more complicated than the mechanics of objects. So compared to the living world, physics has this simplicity of being a kind of clockwork, of making everything reducible to movements, shocks, things… I don’t know to what extent this image is irreducible and that’s why it’s richer.

-B. A.: Yes, it’s outside the realm of physics anyway.

-T .F.: Yes, and what’s more, this image didn’t inspire me much emotionally. Except for the aspect of hitting the wall! But what about the four fingers?

-B. A.: Cartoon characters always have four fingers.

-T .F.: Really? He could also have crushed himself like a tomato, only to regain his shape… that happens too, doesn’t it?

-B .A.: But that’s a classic image, if you like! It’s a type of image that comes up all the time in cartoons.

-T .F.: I think that for him to be able to do something like that, he has to be going faster than the speed of sound inside the rock. You could say something like that: he was going very, very fast, but I don’t know exactly how fast…

[SILENCE]

[LAUGHS]

-T .F.: What else?

-B .A.: I don’t know, if there’s nothing there’s nothing there!

[SILENCE]

-B .A.: OK, let’s imagine something else! What could you say about the world from which this image comes, looking at it from the angle of your scientific knowledge?

-T .F.: By imagining that this image is a photo of a world? So forgetting the designer’s intention and all that?

-B .A.: Yes, that’s right…

-T .F.: First of all, there’s mechanical information about the density of the people in relation to the density of the cliffs. If I don’t have more information about the cliff, I’d tend to think that it’s rather soft, and that people have strange ways of protecting themselves from the impact, since they welcome the cliff with open arms. It does tell you something about the nature of the people who inhabit this world, since they look like coyotes… What would I conclude from that? It’s a shame there’s only one shot. We need to see if the same impacts are seen further down the cliff, to make a statistical approach. That’s how we normally do it, even if we don’t have the individual evolution of that particular individual; by seeing the traces of all the other stories, we can reconstruct the evolution. We do this with the stars. Over a human lifetime, a star does not evolve: for us, for example, the sun remains yellow as it is. But by looking at the statistics for all the types of stars we see, we’ve managed to construct a scenario for the evolution of each star. Here we see a yellow sun, further on a large red star, and elsewhere a black hole or a white dwarf. And by reasoning about this existing population, we can construct a scenario to say that stars, as they age, become red giants, and even later a fraction of them form black holes. But with this image alone, it leaves a lot of uncertainty.

[SILENCE]

-T .F.: No braking marks, eh? In fact, my approach is more befitting an insurance adjuster than an astrophysicist. What I don’t understand is that normally, when you run very fast, your ears are blown back by the wind. But not in this case… If I step outside my earth mechanics logic, I immediately fall back on the symbol of hitting the wall. It’s true that there’s a comic aspect to the scene. But I well remember the pleasure of seeing this kind of scene in cartoons and finding it funny… perhaps the sequence that leads to the image is missing. There’s nothing comic about it for me…

-B .A. : I quite agree… This image, on its own, is not funny. It’s rather harsh…

[LONG SILENCE]

-T .F.: To come back to this idea of analysing the image and knowing whether we can reduce reality to a finite or infinite number of pieces of information, perhaps it’s not a question of reducing reality to a finite number of orthogonal directions, and therefore knowing whether we can know everything about something, whether it’s an object or an activity. But what bothers me is to think that there are people – let’s talk in terms of communities of people – who have such specialised knowledge that it gives them a perspective that is completely alien to mine. Typically, this friend of mine who does lighting, I’m a complete stranger to her field, and it bothers me not to be able to talk to her about it.

-B. A. : It’s funny that you react like that, because you’ll never know how to drive a bulldozer, for example…

-T .F.: Why not?

-B .A.: Or maybe you will, but if you know how to drive a bulldozer you won’t know how ants reproduce… I get the impression that you’re living in a fantasy of the ‘honest man’, the Humanist who knows everything about everything.

-T .F.: It’s true, it’s a pure fantasy…

-B. A.: And even someone like Leonardo da Vinci, who is always presented as an architect, painter, draughtsman and engineer – in other words, the perfect example of the humanist – what did he know about all the human knowledge of his time, one millionth of it? And knowledge isn’t just scientific, it’s also what people experience… You can’t know someone’s pain, someone’s pleasure…

-T .F.: No, but I was careful to separate what is emotional from what is strictly knowledge…

-B .A.: Yes, but even so… But I think we talked about that a long time ago. In any case, what you say reminds me of something very important in my work. It’s the fact that I’m very determined not to specialise. I refuse to develop a style, to develop technical knowledge, to develop a single way of doing things in fact.

-T .F.: Because you think that to develop would be to confine yourself?

-B. A.: Yes, and at the same time I’m not looking for exhaustiveness or totality, absolutely not. Generally speaking, I’m opposed to this idea of ultra-specialisation, and we live in a world of ultra-specialists… That’s why I like the fact that you, an astrophysicist, play the trumpet with Tarace Boulba or take part in choreographic projects…

-T .F.: I specialise in a succession of things, even if they’re superficial specialisations.

-B. A.: Yes, and I do successive non-specialisations. I learn what I need just enough to do something.

-T .F.: And you don’t get the pleasure of meeting communities of people… For example, I laid a parquet floor in my house, the old-fashioned way, by nailing it down. I used two thousand nails and it took me ten days to do it, whereas there are nail gun techniques that are quicker… But afterwards, when I meet a craftsman who makes parquet floors and I tell him that, well, he kisses me… Or he tells me that I’m a bit of an idiot, because he does it with a spray gun. And you talk about purpose and efficiency.

-B. A. : Yes, I know, I’m exaggerating…

-T .F.: There are human relationships, social differences, class differences and differences in know-how, and all of a sudden you have barriers coming down, and I’m very sensitive to that. I’m not sure that for me the aim is human relationships, because I’m also concerned about technical aims. But for example, I had a lot of trouble soldering the printed circuits for a gyroscopic chair I’m making. It was long and hard work, and where I work there are people whose job it is. And when you talk to them about it, and they realise that you know what they’re doing, it completely changes the relationship.

-B. A. : Yes, yes, I agree with that! But for example, there are loads of things I can’t do, or can’t do in a way that satisfies me, so if I have the means, I get people to do them, and I love seeing guys do things I can’t do. But precisely this project of discussing an image is part of this desire for non-specialisation, and also a desire to link things that aren’t usually linked: an artist and an astrophysicist, an astrophysicist and a cartoon image. Except that it’s not a question of technical skill, but simply of creating meeting points between people through an image.

Interview with Nicolas Orlando

-Nicolas Orlando: First of all, as soon as I see the image, it makes me smile… I find it quite comical, you recognise it straight away… Bill the coyote? No, what’s his name?

-Boris Achour: In French, we just say le coyote, but otherwise it’s Vile Coyote? in fact, I don’t know if it’s been translated into French.

-N. O.: So it reminds me of that cartoon, the infernal chases, the desperate ingenuity of that coyote, so at the beginning, in terms of sensation, it’s a feeling of well-being.

-B .A. : A feeling of well-being???

-N. O.: Yes, because at first it’s funny, it brings back memories of my childhood, which made me laugh, and I can still see the coyote’s face, it’s very visual…

-B. A. : As a memory?

-N. O.: Yes, it’s very visual, and I think the expression is very well done, the arms crossed, all the limbs spread, the tail, the fingers, the toes, everything is spread, even the cheeks… you recognise it straight away… So initially a feeling of pleasure, but in relation to my work, my profession, it’s an image that can be transposed into a much darker context, which is in fact that of psychiatric confinement, I find that it makes quite a harsh image, a bit desperate of a certain confinement. So why confinement! First of all, the first form of confinement is that of the walls. You can see that there’s a facade, he can’t get through, he has to get inside, there’s no other way out… where I work, there are walls, and there are a lot of patients who would like to get inside the walls like that, and in that sense it’s a much darker image, especially as there’s no light behind it.

-B .A.: Yes, it hasn’t gone through the wall, it’s inside it.

-N. O.: And by transposition, we can go even further, and that makes me think of the double psychiatric confinement, i.e. there is the psychiatric confinement as we see it, the physical confinement in the hospital but also the psychological confinement in their own suffering. They’re locked up, they’re trying to get out… and it shows the desperate side of things… so if I transpose that to what I do on a day-to-day basis, I find it very bleak. But there’s a positive side to it: he did get through… from the point of view of confinement, he did get through the wall. So I don’t know where the coyote is, but he got through the first part of the wall. In the sense of confinement, there’s a positive side to this, a hopeful side, because he’s crossed over into another dimension…

-B. A.: But you remember that cartoon, do you know why it ended up there?

-N. O.: I can imagine a scenario?

-B .A.: Yes.

-N. O.: Initially I thought he was running, missed a bend and that was it… or maybe he was playing with a catapult…

-B .A.: Yes, that’s it, I haven’t seen that one exactly, but that’s it. This image comes from the fact that he tried to catch the bird, failed as always and hit the wall. And in this cartoon, it’s a never-ending thing, he tries each time, it fails each time, and he tries again. And I think that this could be something interesting in relation to madness, or in relation to imprisonment, because this coyote is not locked up within four walls, but he’s locked up in something else…

-N. O.: Oh yes, in his obsessive idea of catching the bird.

-B .A. : Yes, and he too is doubly trapped…

-N. O.: Yes, completely. He’s trapped in this idea, he can’t get out of it and he suffers from it. And that’s what makes us laugh too, and what drives the cartoon, his desire to catch Bip-Bip, and we know it’s going to fail every time.

-B. A.: There’s something else that interests me in this image, and that’s the relationship to the body that it creates, the fact that the body bumps into things. Earlier, you sounded a positive note when you said: he’s gone into something else, but he’s still stuck in twenty or fifty centimetres of rock and the next image, he’s going to fall back or, as he never dies, the scene stops there and the next image we’ll see him whole and normal, ready to start again.

-N. O.: Yes, if we stick to cartoons!

-B. A. : Yes, of course, but in relation to your practice, what could you say about physical relationships, relationships with the body? Of course, I imagine there are lots of different cases, but…

-N. O.: What’s noticeable is the scattered aspect, the dispersion of the body, the fact that it’s embedded in the wall, you can see its limbs being torn apart… for me, it reminds me more of the anguish, the psychotic anxiety of patients who can’t find their limits, who are handicapped by a lack of knowledge, when they’re very ill of course, of their body, or rather of the limits of their body. They can’t work out how far their body goes. At times they may not know whether the wall in front of them is part of their body or not, and they squeeze things, they squeeze things a lot. They squeeze their hands when they’re held out to them, and they need to feel what they’re hugging, or what’s hugging them, to be helped to feel their bodily limits. Because in fact, they’re completely scattered, it goes in all directions. And this image of dispersion is somewhat recognisable in the fact that the coyote is embedded, in an astral way, it also goes off in all directions. And then what’s notable is that here we can see the bodily limits, they’re very well drawn, and it’s quite funny, this mixture of dispersion and very clear and precise bodily limits. In the sense of the psychiatric pathology of schizophrenia, it reminds me of dispersion.

-B. A.: And what exactly is this dispersion, this absence of limits?

-N. O.: First of all, it’s a phase, an acute phase, that belongs to a very specific psychiatric pathology, which is schizophrenia. There are several types…

-B. A. : What’s the etymology?

-N. O.: It comes from the Greek phrenos, the mind, thought, and skhizein, which means to split. So it really means what it says: split mind. And it’s not to be understood in the sense used in TV films, or in Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde, the good day and the bad night, a sort of dual personality, that would be more akin to hysteria, but schizophrenia is: at the same moment, at the same instant t, a dispersion, a splitting of the mind, of all the components of the mind, the emotional component, the intellectual component, therefore the reasoning, the behavioural component. So, to take a very simple example, someone can be laughing when they’re in a great deal of pain.

-B. A. : They are several things at once? Or do they feel several things at once?

-N. O.: They feel one thing and its opposite.

-B .A.: So, to use your counter-example, they are Jekyll and Hyde at the same time…

-N. O.: That’s right, they’re several things at once, hatred and love, they want to go forward and they go backward, they want to do something and they do the opposite, they want to love someone and they hit them, and so even to think sentences are dissociated, syntax is dissociated, they’re incapable of organising words to make a coherent sentence… And the words themselves are split, they invent words, it’s schizophasia… So it’s dissociation at every level…

[LONG SILENCE]

vN.O.: I look at this image and… yes, there really is an image of crucifixion. The arms are really spread out like in a crucifixion… In fact, you can’t see the body, you don’t know where it is, you can’t even make it out. But despite everything that’s been said, I can’t give this image a completely negative meaning. I don’t have a feeling of displeasure when I look at it, I have more a feeling of… it makes me laugh… you get the feeling that he’s untouchable, that he’ll never be broken… We know it’s not serious and that’s why it makes us laugh, I think… we know he’s going to be OK… if we saw the same image of a guy stuck in a car on the motorway, we wouldn’t feel that way…

-B. A. : But when you say that people with schizophrenia can feel contradictory things at the same time, I get the impression that people without schizophrenia can feel that way too, don’t you? Or maybe it’s a question of degree?

-N. O.: Yes, if it’s just a question of focusing on feelings, in a way… you can love someone and hate them at the same time. But in schizophrenics, the ability to reason is not intact.

-B. A. : And how do these people cope with this?

-N. O.: Well, it’s awful! It’s extreme suffering, torture; they can’t formulate correct sentences, they can’t put their minds together coherently.

-B. A. : There’s no unity?

-N. O.: There’s no unity, it’s complete dissociation, and in fact it’s called dissociative syndrome.

-B. A.: And are they aware of this?

-N. O.: It depends on the stage. In schizophrenia there are two profound pillars, initially there’s dissociation, and then another problem is grafted onto it, which is the delusional syndrome. There are several mechanisms of delusional ideas, which can be auditory hallucinatory, they can hear sentences, words, or have visual hallucinations, but this is quite rare, or imaginative, they imagine… or intuitive, i.e. they are persuaded, they feel very strongly as we have an unshakeable conviction, certain things, or it can be interpretative hallucinations, they interpret from a real or hallucinatory fact, in their delusional sense. They are completely dissociated, at the level of the mind, and dispersed by the whole delusional syndrome. And it’s an awful torture because they can’t rest, there’s no rest…

-B. A. : I’m going to ask you a question that you might find stupid, or even shocking, but hey… is there anything positive, anything good, that can be found in schizophrenia? Or rather, can schizophrenia help us to understand and see the world differently?

-N. O.: What could be positive… for ordinary people to realise that they are not schizophrenic, that they do not suffer from this dreadful disease, and to be happy about that?

-B .A.: Well, that’s in a nutshell…

-N. O.: Otherwise, it opens up a whole new world. If the schizophrenic manages to structure his mind and be creative – and that’s what art therapy is all about – he can create things that no-one else could. Perhaps it’s also because of the delusional syndrome, they have an enormous creative capacity, they’re completely inhabited by their delusions…

-B .A.: Yes, but that’s not how I meant it, I was talking about people who aren’t schizophrenic. Maybe the answer is no, that there’s nothing positive to be gained from this illness, I don’t know… It’s a naive and hard question, like saying: what’s good about cancer?

-N. O.: But cancer, or rather the way it works, I think we use it in certain therapies. Cancer is the inability of cells to recognise their limits to growth. We’re made in such a way that when cell x touches cell y, they stop growing, and cancer means that this contact between cells doesn’t stop proliferation, so we can use it to create proliferating structures of cells that we might need…

-B. A.: Well, that’s what I’d like to know about schizophrenia.

-N. O.: It’s all masked by the suffering of the individual, but I think that … how can I put it … I think that in exceptional situations, this kind of person could be useful to a community…

-B. A. : For example?

-N. O.: It’s only relatively recently that schizophrenia has come to be seen as a disability. Before that, or in other cultures, it was considered to be a direct access to the afterlife, a privileged group of people who had contact with God and the spirits. Schizophrenia exists everywhere, even if it’s expressed differently, and it’s often linked to mystical themes… and it used to be used. In any case, in schizophrenia, you don’t have delusional upsurges for months on end, they come in waves and spikes, and these delusional upsurges can be interpreted as access to God… Schizophrenics very often have a megalomaniac feeling, they see themselves as prophets, the chosen ones, who must spread the good word, they have a sort of divine mission…

-B. A.: But today, in our society, do you see anything positive in schizophrenia, or in one of its aspects, something that could be useful?

-N. O.: No, I don’t know, I’ve never asked myself that question. But at the same time, schizophrenia is a young illness, discovered very recently, so we’re still confined to the human being as a whole. We don’t know the origin of schizophrenia at all, there are no biological markers, unlike other illnesses. There are no biological markers, unlike other illnesses. Moreover, it’s a diagnosis of elimination: we do all the physiological tests to look for an illness, and if we don’t find anything, we call it a psychiatric illness. And that’s what psychiatry has developed around. And it’s looking for its biological marker.

-B. A. : Why does it need this?

-N. O.: To treat. To find out where it’s coming from, to know where it’s coming from, and then to treat it.

-B. A.: And you think that in order to treat these illnesses, we need to find their physiological causes? Well, I don’t know much, if anything, about all this, or how the brain works, but do people think that schizophrenia has a physiological cause and we haven’t found it yet, or do some people think that this illness has no physiological cause?

-N. O. : There are several schools of thought. There’s a whole school of psychiatry which, notably through analysis, completely denounces the organic link with the disease, and then there’s another school, notably American and British, driven by the economic impetus of the laboratories, which tries to show that it’s a disease like any other, which can be treated medically. And so these people think that it’s not only biological but also genetic…

-B. A.: And you, even though you’re not a researcher, what do you think about the causes of this disease?

-N. O.: I think… with all the complexity of the human brain, with all the diversity of people, despite all that, in schizophrenic patients we find normotypes.

-B. A. : Sorry?

-N. O.: Normotypes, in other words, patients obey classifications that are found in hundreds of people who, on the face of it, have nothing in common. This means that there is a common core to this disease, and to explain this common core I can only see this biological approach… I don’t know if it’s genetic, hormonal… but there is a biological background. Which doesn’t explain everything, so it’s a Norman answer…

-B. A.: And are you familiar with the experiments carried out, for example, by someone like Félix Guattari at La Borde?

-N. O.: That sounds familiar, that’s anti-psychiatry?

-B .A.: Yes…

-N .O.: I don’t know it very well, but I think it refers to less serious mental pathologies. And then anti-psychiatry was based on the anti-institutionalisation of psychiatry, the anti-asylum life in short. And indeed on certain points, we’re right in the middle of it, there are bills being drafted that want to destroy the psychiatric hospital, with good intentions… we want to reintroduce… we want to resocialise the madman, we don’t want to keep him away like before. Basically, in the Middle Ages, mad people lived in the forest, or in dungeons, then they were parked in large psychiatric hospitals, and there are a lot of them in the Paris region, and now the idea is to deinstitutionalise them, to reintroduce them into the city, and ensure that they adapt as much as possible, like any citizen, and therefore close these psychiatric hospitals, which are full of history and suffering. In fact, we’re attacking the concept of confinement rather than mental illness itself, throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

-B. A.: You mean that they’re good feelings, but they run the risk of…

-N. O.: It works for a certain fringe of people who are ill, yes, it’s good… in fact, someone who suffers from minor depression, or schizophrenia that isn’t very incapacitating, there’s no point in them going to a psychiatric unit where they’re locked up with the crazy people. But there will always be a certain number of mentally ill people who are very ill, and for whom this desire to integrate into the community cannot be achieved, at least not in such a radical way… and in any case they go to prison. Where crazy people go nowadays is either in the underground or in prison…

-B .A.: And why do these people end up in prison?

-N. O.: Because their delusions, their associative syndromes, their anxieties and their destitution automatically lead them to commit completely mad acts.

-B. A.: Violent?

-N. O.: Yes, often violent, or simply criminal, so they end up in prison.

-B .A.: Rather than in… medical care? Why is it that it’s the justice system that looks after these people and not health, or medicine?

-N. O.: Well… we’re back to this historical development, but it’s a departure from your image…

-B .A. : No, but that’s OK, it’s just a starting point, this image…

-N. O.: O.K…. Until the Revolution, the mentally ill were considered to be citizens in their own right, just like anyone else. In other words, if they killed someone or committed a crime, they were sentenced like anyone else. And thanks to the philanthropic ideas of the Revolution, the great alienists of the time, i.e. the chief doctors of psychiatric hospitals, wanted to put these ideas into practice and asked for certain points in the penal code to be revised so that a mentally ill person would not be held responsible for his acts. This meant getting the patient out of the legal system and into the healthcare system. But this came very late, well after the Revolution; the first psychiatric law dates from 1836. So it dates back to the philanthropic ideas of the Revolution, even though the Greeks were already talking about it in Antiquity: « a madman must not be judged like a sane man ». And so, on the strength of these ideas, there were laws and articles, for example article 64 of the Napoleonic Code in 1834, which is now article 122, and which defines psychiatric non-litigation and criminal irresponsibility. All criminal cases must be examined by psychiatrists, and at the end of this examination, the judge must ask for the opinion of the commission of expert psychiatrists, who can ask for the person to be relieved of responsibility, by virtue of this article 122. And then the judge is sovereign, deciding whether or not to follow the opinion of the experts. It turns out that because of the media coverage of this kind of case, especially as they are often extremely spectacular, because the psychotic mental patient kills very violently, even more violently than the others, he doesn’t realise anything, he’s completely uninhibited… and so because of this media coverage and this spectacular aspect, the dismissals, even if they have been pronounced by the experts, are not recognised, and we fall to 1% of dismissals.

-B. A.: You mean that out of 100 cases in which the experts declare that the defendant is not responsible, the judges only follow their advice in 1 case? So in 99% of cases, the judge does not follow the experts’ advice?

-N. O.: Well, that’s it… But then there are several levels… The experts also recognise that certain mental pathologies can be treated in prison. You should know that some prisons have psychiatric departments where mental illnesses are treated, but only for patients who agree. For the time being, people in prison cannot be treated under duress, but this is about to change… But for the moment it’s not possible… yes, so… all the dismissals have reduced enormously, and so a criminally mentally ill person no longer leaves the legal system to go to health, but he stays in the legal system until the end.

[SILENCE]

-B. A. : That’s completely incredible… But you, as a doctor, don’t find it…

-N. O.: I don’t know… I don’t know whether I’m giving you an honest answer or not!

-B. A. : Well, yes!!! Give me an honest answer!

-N. O.: What can I say? I’m a doctor, so I’m quite philanthropic, I want to help my fellow man as much as I can… but the problem is that there are flaws in the system. But the problem is that there are failings in the system. When a case is dismissed, the madman leaves the legal system to go into the psychiatric system, but in psychiatry, there are cuts in beds, cuts in staff, and we can’t provide sufficient follow-up. And the terrible thing is that the patient kills again… and I find that unacceptable…

-B .A.: So we put them in prison to prevent this!

-N. O.: Yes, we put them in prison to prevent this from happening. In fact, we need systems where the mentally ill can be treated in prison.

-B. A.: Or there should be enough hospital beds and staff. That’s the main thing, isn’t it?

-N.O.: Yes, but that’s impossible, because we’re in a movement towards deinstitutionalisation, downsizing, reducing beds and cutting costs. Schizophrenia affects 1% of the French population, and it’s the same percentage in every country, in every culture…

-B. A.: That’s a lot, isn’t it?

-N. O.: It’s enormous! Fortunately, they’re not all dangerous; there’s a tiny proportion who are dangerous, and this tiny proportion who commit dangerous acts need to be monitored. And sometimes they’re not.

-B. A.: You may find the comparison exaggerated, but it’s like putting HIV-positive people in jail because there aren’t enough hospital beds and they could be a danger to others. It’s a bit of the same logic, isn’t it?

-N. O.: Yes, but there has to be a logic of treatment and prevention. And that’s very difficult, because everything is linked, it’s a chain. The mentally ill exist and if we close hospitals, they have to go elsewhere, and elsewhere it’s the underground and prison. I think it’s great that mental health specialists have managed to change the penal code, to ensure that someone considered irresponsible can get out of the legal system, but… we can’t decide anything, it’s political. Of course, if we opened up a lot of beds and created monitoring and prevention structures, there wouldn’t be a problem. Because what does a mentally ill person in prison do? They don’t understand why they’re in prison. They don’t work on their mental illness, no one helps them, they double their sentence, because in prison they hit, they’re aggressive, they can’t control themselves, and when they get out, they’re the same. So in terms of society, when he gets out, he’s dangerous… The problem is that psychiatrists themselves, and the rest of the nursing staff, reject dangerous mental patients. Someone who looks after a mentally ill person, who tries to treat them, is driven by a feeling of empathy, but if the patient is aggressive and violent, you no longer want to help them, there’s no more empathy. So there’s rejection. And psychiatrists and healthcare staff are quite happy for these people to be in prison. They don’t want to see them at all.

-B. A. : So you’re aware of that!

-N. O.: You can see it. There’s a health map and each geographical area has its own hospital and department. And when a patient commits a criminal act, if it’s simply a question of behavioural problems on the public highway, he goes to the sector he belongs to, the one that corresponds to where he lives, but if he commits a serious act, he goes to prison, where there’s a commission of experts, and if the experts recognise that the patient is not responsible, and if the judge follows them and recognises that there is no case to answer, the patient is released from prison and arrives, for example, in our psychiatric unit: He has to go back to his sector, and the sector doesn’t want him, they say: no, we don’t want this patient any more, he’s too dangerous, too aggressive. There’s a rejection of the mentally ill, no feeling of empathy… And in a way, that’s human. And my job is to re-establish links between the patient and his sector, which doesn’t want him. And that’s difficult… It’s all the more difficult when you know that the patient is going to do it again, or is likely to do it again… And so we’re in a surveillance mode… It’s a terrible system…

-B .A. : How do you feel about it? It sounds completely bleak and demoralising!

-N. O.: Overall, we can see that some patients… you need at least ten patients who make it through to pass a failure. One failure can call into question ten patients who have come through it, so we’re much more sensitive to failure than to patients who have come through it. But there are still patients who have been very, very badly, seriously ill, seriously dangerous, and who come through and live normally… well, almost normally.

-B. A.: In practical terms, how do you treat these patients, given that you say there are no organic substrates?

-N. O.: There are no organic substrates, but we have nonetheless found drugs that greatly reduce delirium. And dissociation to a greater or lesser extent.

-B.A.: So you treat the effects without knowing the causes.

-N. O.: Exactly. Moreover, psychiatry has become a symptomatic discipline: we treat the symptoms. If you have insomnia, we treat insomnia! If you have delusions, we treat delusions! If you are depressed, we treat depression! We only treat symptoms. It’s very pragmatic.

-B. A. : And for you it’s a stopgap? Or is it a good thing?

-N. O.: Yes, it’s a stopgap, but a perfectly honourable one. The patient suffers less, and the most important thing is the patient’s suffering.

-B. A. : For you, as a doctor! Because I imagine that judges don’t think like that…

-N. O.: Oh yes! It’s different! It’s at a different level! Because there’s the mentally ill and the dangerous mentally ill. And for me, the most important thing for the mentally ill is their suffering, and for the dangerous mentally ill, the most important thing is how dangerous they are.

-B. A. : And how do you differentiate between the two? Is a dangerous mental patient primarily dangerous or primarily suffering?

-N. O.: Yes, that’s a good question.

[SILENCE]

-N. O.: In any case, if we want to reduce their dangerousness, we have to treat their illness. You have to, because dangerousness is fuelled by mental illness. And the paradox is that you can be led to treat people without any feeling of empathy. You take it out on yourself…

-B. A.: You see, in relation to the question I asked you earlier, about whether we could draw something positive from schizophrenia, this idea of being able to help people without necessarily feeling empathy, I think it’s an interesting thing, don’t you? From an intellectual or philosophical point of view?

-N. O.: Yes, it’s a bit interesting, but you lose a lot in terms of quality of care. There has to be a feeling involved, something emotional. Without empathy, it’s a bit mechanical. It can be done… But in fact if there’s no empathy it’s because we’re trying to preserve ourselves as best we can. It’s like being asked to treat Mengele. We do it because we’re doctors, but… well, that’s an extreme example.